Mastery of Cognitive Skills

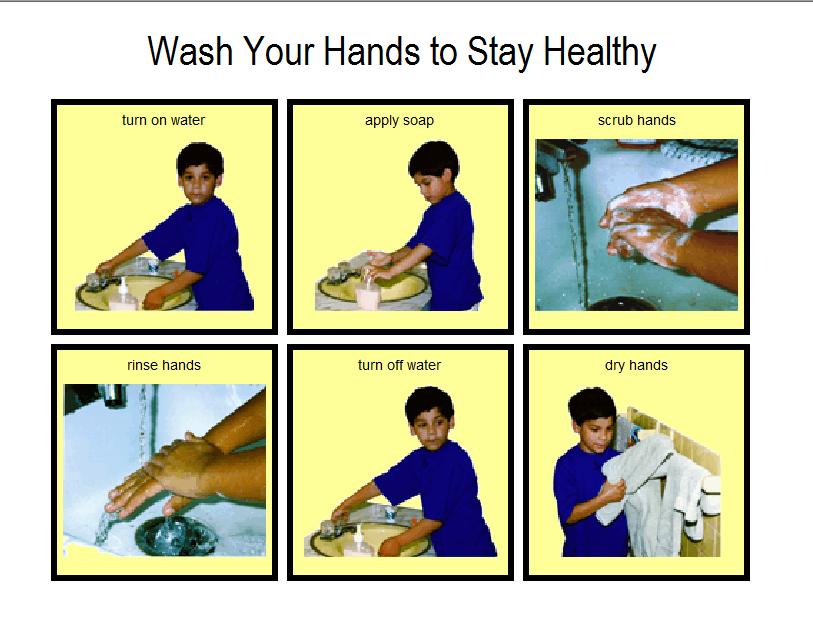

When teaching high-level cognitive skills, it can be incredibly difficult to determine when you are finished. For example, let’s say we are teaching a learner the concept of before / after. We might do this by showing the learner a sequence of pictures like this:

We might teach this by asking the learner to:

- Point to what happened before the boy rinsed his hands.

- Point to what happened after the boy applied soap.

- Tell me what happened before the boy scrubbed his hands.

- Tell me what happened after the boy turned off the water.

After the learner acquires this skill with many sequences and shows generalization to novel, untaught sequences, we might think we are done. He now “understands” before / after. He can do it with sequences we have never shown him before! This skill is mastered! Time to celebrate.

But if you have been around for a while, you probably know it is too soon to celebrate. We are just getting started. We now need to teach:

When did the boy turn on the water?

The expected answer might be:

Before he applied soap.

OK, done! The learner mastered the before / after questions with “when” and it was integrated with the previous four questions. He showed generalization to novel examples that we didn’t teach. He has truly got it now!

No, probably not. Go ahead and celebrate some, but there’s still more to do. How about things like this:

What did the boy do before he dried his hands?

Or:

Before you touch your nose, clap.

Clap after you touch your nose.

Or:

The learner is playing a game with a group of friends. Who went before Joe? Who goes after Sally?

What if we combine it with other difficult concepts, like pronouns?

Who gets a turn before you? Whose turn is it after me?

And what about remote events:

What are you going to do after school?

What did you do before school today?

This kind of problem is present in virtually any teaching situation from preschool through graduate school. If you are interested in a deep dive, check out the book Theory of Instruction. Unfortunately, that book requires a few lifetimes to study. For some immediate teaching resources for elementary school children, check out the Direct Instruction programs written by Engelmann and colleagues.

Behavior analytic services should only be delivered in the context of a professional relationship. Nothing written in this blog should be considered advice for any specific individual. The purpose of the blog is to share my experience, not to provide treatment. Please get advice from a professional before making changes to behavior analytic services being delivered. Nothing in this blog including comments or correspondence should be considered an agreement for Dr. Barry D. Morgenstern to provide services or establish a professional relationship outside of a formal agreement to do so. I attempt to write this blog in “plain English” and avoid technical jargon whenever possible. But all statements are meant to be consistent with behavior analytic literature, practice, and the professional code of ethics. If, for whatever reason, you think I’ve failed in the endeavor, let me know and I’ll consider your comments and make revisions, if appropriate. Feedback is always appreciated as I’m always trying to Poogi.

Unpredictable

There is an old saying that predictions are difficult, especially about the future. Many times, when we run into problems, we blame random chance as the cause of the problem. For example, we might have scheduling problems due to random unpredictable events:

- Three staff are out sick on the same day.

- A critical staff person leaves for more money or to go to graduate school.

- Several staff members are on maternity leaves.

Sometimes the children we serve have problems that we blame on random chance:

- He was asking to go outside, but we had to say no because it is raining.

- I was there to do the session, but he had to use the bathroom and I missed most of my time with him.

- We were working on the iPad, and the battery ran out just when we were going to work on the reading program.

Sure, random unpredictable things do happen and you can’t prevent all of them. The mistake is thinking that the event was unpredictable and there is nothing that I could have done to prevent all the problems that the random event caused. I just have to deal with it.

No, you don’t. You might not be able to predict the time exactly, but you know that sometimes multiple staff will get sick on the same day–at least occasionally. What’s the plan to handle that? Why can’t the child be asked to go to the bathroom before critical sessions?

Having a plan–a system in place to handle these types of “unpredictable” events–often means the difference between success and failure.

What’s Appropriate?

Schools are supposed to provide children with disabilities with FAPE (Free Appropriate Public Education). But frequently, parents of children with disabilities and school districts don’t agree on the meaning of the word “appropriate.”

There is a lot of legal opinion on this topic that I don’t intend to get into here. For now, the main point is that there isn’t an agreed-upon standard to determine if a program is appropriate.

There are some generally accepted rules. For example, the school district is not required to provide the “best,” only what is appropriate. On the other hand, if a child is making no progress or very minimal progress, the program is clearly “not appropriate.” This can sometimes be an adversarial process; schools and parents sometimes turn to outside evaluators to help make the determination.

When you have a subjective standard like this, it is impossible to prevent huge biases from entering into the decision. This is especially true when the results of an evaluation can mean very large sums of money (e.g., if the evaluation causes a school district to outplace a student to a private school for example) and loss of control over a program.

I used to be one of the expert evaluators that would give an opinion on whether a program was “appropriate” or “not appropriate.” Although it can sometimes help children get better programming, I rarely agree to do these anymore. I just didn’t enjoy the work. I’d rather be the person doing the programming, and then let someone else evaluate my work. I’ll Poogi more that way, too.

The key lesson is that these decisions are rarely made solely based on the data (even if the issues are primarily decided by BCBAs). I’ve seen terrible programs survive an evaluation as appropriate. I’ve seen excellent programs be deemed not appropriate. It is not enough to master data analysis; we must learn to work in complex social environments too.