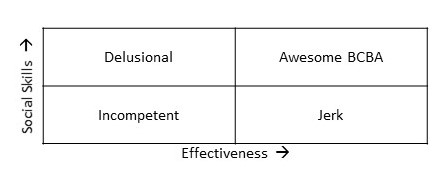

The BCBA Effectiveness/Social Skills Matrix

Several times, I have seen programs that are very ineffective, yet seem to have high parent satisfaction. Other times, I have seen programs that seem very effective, yet have low parent satisfaction ratings. How does that happen?

I’ve heard you are not a real consultant until you make your own 2 X 2 matrix explaining a phenomenon. So here goes:

We may think that parents, teachers, and other stakeholders base their satisfaction ratings of applied behavior analysis programs solely on how well they work; as if they were buying a toaster. But people don’t even judge toasters solely on how well they work. How easy was it to navigate the toaster company’s website? Did it come when promised? How friendly was the customer support? Was it easy to return a damaged product? Etc. etc.

In my view, stakeholders will judge applied behavior analysis programs based on at least two factors. First, how effective is the program? A program that clearly shows no benefit will be unlikely to obtain high satisfaction ratings. Second, the social skills of the BCBA and other members of the team. Of course, these two factors don’t act completely independently, but are synergistic. A highly effective BCBA probably has to respond to upset parents and teachers less frequently. A highly socially skilled BCBA probably has teachers and parents who implement programming better, and thus has higher effectiveness. See this article for an excellent discussion.

If a BCBA falls low on social skills and low on effectiveness, they will fall into a category we might label as incompetent (Lower left panel). Very few stakeholders will be satisfied with services if this is the case.

But if a BCBA is highly effective, yet has poor social skills, this person might still have poor stakeholder satisfaction ratings. This BCBA falls into the category we might refer to as a jerk (right lower panel). Even if a program shows outstanding progress, that doesn’t mean you can act like Barry from the Bronx. Now, Barry the BCBA from Bethel, Connecticut realized that, and has Poogi-ed significantly. In other words, BCBAs need to develop a variety of social skills in addition to clinical skills. This has been studied in the medical profession. For example, problematic social skills seem correlated with medical malpractice claims.

OK, that makes sense. If you act like a jerk, then parents and teachers are not likely to be satisfied regardless of how effective the program. That might explain effective programs with poor satisfaction ratings. But why would low quality programs have high satisfaction just because they like the BCBA? If the program isn’t working for the kid, people are still going to be upset. Right?

Maybe not. Most programs are not completely ineffective and can tell a good story. The child has made some progress. It is just that a higher-quality program would have made much more progress. That isn’t easy for the average stakeholder to determine. If you don’t have the experience to know what’s missing, you might be satisfied with the minimal progress you are seeing. That’s why I refer to this category as delusional (upper left). There might be no one complaining; everyone loves the BCBA, but that doesn’t mean the services are high quality.

Of course, everyone should strive to be in the upper right panel (Awesome BCBA) with high levels of effectiveness and high levels of therapeutic social skills.

To me, the lesson is that while satisfaction ratings are essential data, they are easily biased by (a) How much people like the staff, and (b) The amount of experience the rater has to evaluate whether the program really is high quality or not. They are extremely useful, but caution is warranted when interpreting those data.

My Very First Assignment

The Lessons I Should Have Learned

As a young graduate student in behavior analysis, I worked as an intern at a large institutional setting to gain experience. Some of these types of settings were incredibly low quality by modern day standards—actually, by any standards. I didn’t know that at the time, as I had no experience working with individuals with developmental disabilities. The clients were diagnosed with numerous types of disabilities ranging from very mild to very severe, both psychiatric and developmental. I got immediate experience with a very large number of different types of diagnoses.

My first assignment was to run the “reward room.” The institution was starting a new token economy. That meant that the teachers would provide the clients with tokens. When they earned enough tokens, they would trade them in and be taken to my room to enjoy the rewards for a few minutes.

I got there early on the first day to set up the reward room. I set up video games and I made sure that I knew how to work them. I had games and toys available. I had a large candy bowl of individually wrapped candies available. I didn’t receive any training. My only instruction was “just try to make sure the clients enjoy their few minutes in the ‘reward room.’ “

The first client came in with the teacher who was much bigger than me. The teacher told me how well he had done that morning, and then left me alone with the client. I enthusiastically greeted the client, but the very second the teacher leaves, he charged at me, knocked me over, and rushed immediately to the candy bowl. He started grabbing large handfuls of candy and shoving them all in his mouth with the wrappers still on. Panicked, I attempted to stop him from choking himself and called for help. The reward room only lasted a week or two at this institution, as it was clearly a poorly thought out plan.

I have often thought of this experience as a trial by fire. The extreme pressure and stress made me want to be successful and help people live better lives. Occasionally, I used to say you aren’t a real behavior analyst until you have an injury story. That is the culture in many places; sometimes you’re going to get hurt, it’s just part of the job. Although few people are likely to have a first experience as dramatic as I had, BCBAs are still making similar mistakes today. I hear all the time from staff that they were “thrown into difficult situations” with no training. Just like I was. I hear staff tell me about being in incredibly unsafe situations. Just like I was.

It took me longer than it should have to learn from these experiences. We should never let a staff person work with an individual if (a) They haven’t been trained to criterion on what do and (b) The working environment is not going to be safe for both the staff person and the client. That might seem obvious, but more than 25 years in the field have taught me that it definitely is not.

Does it Have to Get Worse Before It Gets Better?

When providing treatment for problem behaviors, many of us have often taught our parents, supervisees, and others “It gets worse before it gets better.” I don’t know how many times I’ve said this over the years, but I can tell you it is a lot. This is a huge obstacle to successful treatment. The fact that it often gets worse initially leads to safety concerns, lack of buy-in from parents or school staff, restraints, seclusion, and potentially giving up on effective treatments. But now, I think this rule doesn’t have to be true. In fact, it might be that it is rarely true. If so, that would solve many implementation problems.

Why Do Problem Behaviors Occur?

When a child is engaging in problem behaviors, the assumption is that they are getting something out of it. In other words, the problem behavior isn’t just random, but there is a real tangible benefit for the child. Now, this doesn’t deny that some behaviors are related to emotional reactions. Just that the vast majority of problem behaviors can be understood if we understand it from the child’s point of view and figure out what benefits they are receiving from the behaviors.

BCBAs will start by trying to figure out the specifics of what kids are getting out of the problem behavior. In my view, recent research is suggesting that it is rarely just one thing. Most likely it is some combination of events like:

- Not having to do something they don’t want to do.

- Getting to do something they do want to do.

- Getting other people to act in a way they want them to act.

- Getting some physical stimulation that makes them feel good.

Why does it often get worse before it gets better?

Once we figure out the benefits the child is receiving from the problem behavior, we design a treatment to eliminate it. That treatment almost certainly has many parts, but virtually always includes not giving them what they want if they engage in the problem behaviors. In other words, the problem behavior abruptly no longer serves its purpose.

So, what happens when normally we get what we want after engaging in a behavior, and then suddenly we don’t? Think of a time when you bought something at a vending machine and nothing came out. First, you probably tried to hit the button several more times. Next, you probably hit the button harder, got angry and maybe punched the machine or complained to someone. That’s the typical reaction. First, we increase the behavior (hit the button several more times). Then we increase the intensity of the behavior (e.g., hit the button harder, got angry, and punched the machine). But eventually, you stopped trying to get your item out of the machine.

That’s what we expect when we use this procedure with kids who engage in problem behaviors.

First, they will increase the amount of the behavior. Next, they will increase the intensity of the behavior and maybe even have serious emotional reactions. But eventually, they will stop engaging in the problem behaviors.

The Conflict

This put BCBAs in a tremendous conflict. On the one hand, we want to have successful treatment in community settings like schools. This requires obvious things like the treatment be safe; strong support from teachers and families; the treatment maintains the dignity of the child. On the other hand, the research literature seems to tell us that successful treatment often requires a “burst” of responding. Without riding out the “burst,” treatment would simply not be effective in many cases. Of course, some treatment of mild problem behaviors might not have this problem. But many, many children seem to need this. What’s the BCBA to do?

False Choice?

There have been several studies suggesting different ways that treatment might be implemented without having to deal with the burst. I’m no longer convinced that going through the burst is necessary for the successful treatment of problem behaviors, as I’ve seen several successful treatments implemented without it.

It is easy to be fooled by the elimination of problem behaviors that won’t last over time. That’s not the critical factor. In my view, the key to successful treatment depends on the teaching of alternative behaviors that will naturally work in the child’s everyday life. That’s most likely to lead to success in the long run. We have always done that. What’s somewhat new is there might be a variety of ways to focus on the alternative behaviors without the need to create a burst. A few potential ideas include making reinforcement for the problem behavior not quite as good as reinforcement for the alternative behavior or simply prompting the appropriate alternative behavior contingent on problem behaviors. These procedures have the potential to dramatically increase safety. In addition, they might increase the time available for instruction if you don’t have long dramatic episodes of problem behaviors.

We don’t have enough research yet to tell us that we can always successfully treat problem behavior without a burst. It is a critical area for future research. I know several research teams are working on this problem. But for now, it is definitely worth considering all the alternatives and not just assuming it will be necessary. There is strong evidence that the burst isn’t always needed.